The program is funded by employee payroll taxes and administered through the state's temporary disability program. It provides a minimum benefit of $72 and maximum of $752 per week, based on earnings.Child, parent, parent-in-law, grandparent, spouse, domestic partnerVermontAll employers with 10 or more employees for leaves associated with a new child or adoption. All employers with 15 or more employees for leaves related to a family member's or employee's own serious medical condition. Employees who have worked for an employer for one year for an average of 30 or more hours per week.Up to 12 weeks in 12 months for parental or family leave. Allows the employee to substitute available sick, vacation, or other paid leave, not to exceed 6 weeks. Provides an additional 24 hours in 12 months to attend to the routine or emergency medical needs of a child, spouse, parent, or parent-in-law or to participate in children's educational activities.

Limits this leave to no more than four hours in any 30-day period.Child, spouse, parent, parent-in-law.WashingtonAll employers. The FFCRA gives businesses with fewer than 500 employees (referred to throughout these FAQs as "Eligible Employers") funds to provide employees with paid sick and family and medical leave for reasons related to COVID-19, either for the employee's own health needs or to care for family members. Workers may receive up to 80 hours of paid sick leave for their own health needs or to care for others and up to an additional ten weeks of paid family leave to care for a child whose school or place of care is closed or child care provider is closed or unavailable due to COVID-19 precautions. The FFCRA covers the costs of this paid leave by providing small businesses with refundable tax credits. Certain self-employed individuals in similar circumstances are entitled to similar credits.

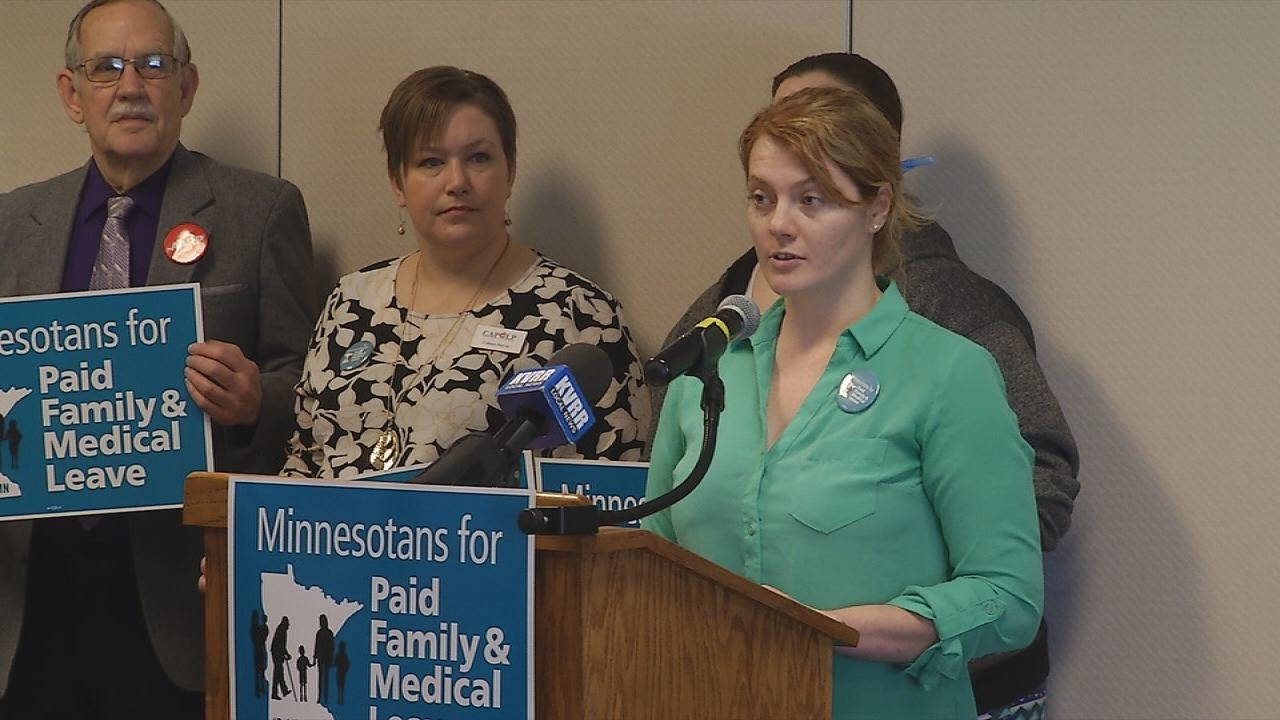

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act requires eligible employers to provide unpaid family leave. However, unlike nearly all other industrialized nations, the U.S. does not have national standards on paid family or sick leave, despite strong public support. Paid leave has garnered attention among the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates, with most expressing support for a national policy, and President Trump has allocated funds for paid family leave in his budget, though the administration has not issued a formal proposal yet. Some efforts at the federal level have begun to gain momentum, including the Healthy Families Act, introduced in the House of Representatives and in the Senate in 2019, which would require most employers to offer workers paid sick leave.

The Federal Employee Paid Leave Act took effect in October 2020 and grants federal employees 12 weeks of paid parental leave following the birth or placement of a child. The most recent nationwide policy reform occurred in 1993, when the federal government passed the FMLA, giving eligible employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to care for seriously ill family members, the arrival of a child, and job protection when an employee returns from family or medical leave. The law applies to public agencies and private employers with 50 or more employees. The FMLA has provided job security to millions of workers who take time off to care for a critically ill family member or a new child in the family.

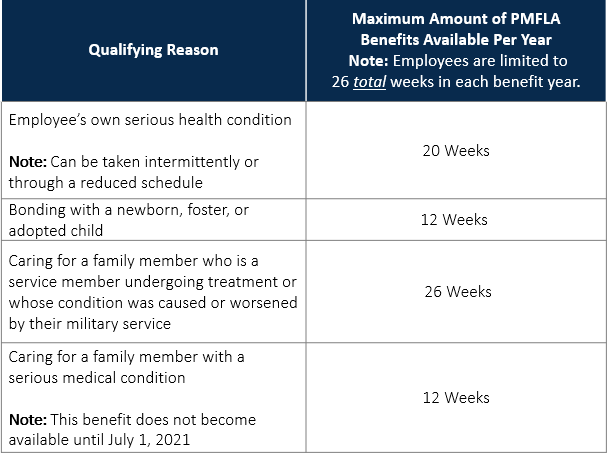

However, only 60% of the workforce is eligible for FMLA protections because small employers are exempt, and even in covered worksites, not all employees are eligible. Since 1993, 15 states and the District of Columbia have expanded unpaid leave benefits beyond FMLA standards by either increasing the amount of leave time offered or expanding the definition of an eligible family member. The earliest version of the FMLA, the Family Employment Security Act of 1984, called for up to twenty-six weeks per year of unpaid, job-protected leave to care for a new child, a child's illness, a spouse's disability, or the employee's own disability.

Most activists actually wanted paid leave, but they worried that such a bill would not pass. Although the FESA was never formally introduced in Congress, it opened a legislative dialogue on family leave and set the stage for future bills. In 1985 Representative Patricia Schroeder (D-CO) introduced the Parental and Disability Leave Act, which mandated eighteen weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave for new parents, as well as twenty-six weeks of leave to care for a sick child or the employee's own temporary disability. The bill could only make it through two House subcommittees before stalling. When a new family leave bill was introduced in the 1986 legislative session, its name was changed again to the Parental and Medical Leave Act. At the same time, the American Association of Retired Persons successfully lobbied to include expanded coverage that would allow employees to take time off to care for a spouse or elderly parent, in addition to a child.

For that reason, the bill underwent one final name change in June 1986 to become the Family and Medical Leave Act. There has been more traction on paid sick leave policies at the state and local level . Eight states' and eleven localities' requirements explicitly apply to public health emergencies, such as closure of a business or child's school to protect public health. All state and all local paid sick leave laws permit use of accrued leave for reasons associated with sexual assault, domestic violence, and stalking, except Pittsburgh's. Current paid sick leave laws generally work on an accrual basis, dependent on previous hours worked. The pay rate and the amount of paid sick time that can be accrued varies by policy.

A comprehensive paid family and medical leave policy would guarantee leave for workers to care for a new child, recover from a serious health condition, care for a seriously ill family member, or address needs arising from a family member's military service deployment. In the spring of 2020, Congress passed temporary emergency paid leave in response to the pandemic that is limited to uses related to COVID-19. It provided 80 hours of emergency paid sick leave and 12 weeks of emergency leave to care for a child whose school or place of care is closed. That law expired on December 31, 2020, and was replaced with a voluntary tax credit.

Although there has been significant progress at the subnational level, most family leave advocates also continue to work toward the ultimate goal of a national policy. In 2015 Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) introduced the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, which provides workers 66 percent of their wages (capped at $1,000 per week) for up to twelve weeks for the same reasons covered by the FMLA. It does not include job protection, but eligibility extends to all workers who pay into and are eligible for Social Security benefits for at least one year. Unlike the state-level policies, the FAMILY Act would rely on both employee and employer contributions of 0.2 percent of wages, capped at $4.36 per week. After being read in the legislature on March 18, 2015, the bill was referred to committee and no further action was taken. At least in the immediate future, a federal paid family leave law is unlikely.

Paid leave continues to be a significant national and local policy issue and has garnered the attention of many 2020 Democratic presidential candidates. President Trump has spoken about the need for supporting working class Americans, and forwarded the framework for a proposal to offer paid parental leave to all workers in the U.S. At this point, the proposal lacks details and it remains to be seen whether Congress will take up this issue, though some lawmakers have introduced legislation.

However, a new policy that took effect in October 2020 provides federal employees 12 weeks of paid parental leave following the birth or placement of a child. Short of that, the movement for paid parental and sick leave will likely continue to be centered on state and local policies or those voluntarily adopted by employers or negotiated through union contracts. Given that most people will need time off during their working lives to care for a personal or family illness, or for a new child, this issue will continue to be a salient concern for working families across the country in the years to come. On the paid leave front, there have been many attempts to build upon the FMLA and enact a national paid leave policy, but no federal legislation has ever been passed. President Donald Trump's budget for fiscal year 2020 included a proposal for paid parental leave for all U.S. workers after the birth or placement of a child.

The budget allocated $20 billion over the next 10 years to fund the program, but a formal proposal has not been issued by the administration. In contrast to other types of leave—in particular, parental leave, which has been studied extensively—family care leave receives much less attention in existing research. While each of the paid family and medical leave laws at the state level includes family care leave, national proposals diverge on this point. Unlike those proposed by President Obama and Secretary Clinton, the family leave provisions proposed by President Trump and Sen. Rubio focus exclusively on parental leave and do not include benefits for employees who need leave to care for a seriously ill family member.

Great paid family leave policies provide ADEQUATE TIME. Policies should meet the needs of new parents, people who need take time to provide family caregiving, and individuals who need time to address their own serious illness. Twelve weeks of paid parental leave and six weeks of family and medical leave is a minimum in order to meet the needs of employees at these critical times. Providing paid sick time to employees reduces the spread of illness, increases productivity, and improves public health. Paid leave policies increase women's labor force attachment and representation in the workforce, which in turn has measurable positive impacts on the GDP. In fact, Cornell University economists attribute the lack of paid family leave and other "family-friendly" policies to the sharp drop in the U.S. female labor force participation rate in the last two decades compared to other advanced economies––from 6th place to 17th place.

Leave policies improve workplace environments by increasing employee retention, morale, and productivity. Only 19 percent of workers in the United States have access to paid family leave through their employers, and just 40 percent have access to personal medical leave through employer-provided short-term disability insurance. Eighty-four percent of U.S. voters support a national paid family and medical leave policy that covers ALL working people to care for a new child; a seriously ill, injured or disabled loved one; or their own health issue. Last year, only 19 percent of civilian workers had access to paid family leave through their employer or through a state program, and only 40 percent had short-term disability insurance for their own personal medical issues. Although federal law currently requires employers to provide unpaid leave to qualified workers, the eligibility requirements exclude about 40 percent of private sector workers.

And nearly half of eligible workers report that they simply cannot afford to take unpaid time off work. One point of difference between the approach taken by other countries and that taken by the United States has to do with the treatment of different types of leave. The U.S. government enacted family and medical leave quite late compared to other countries, and the Family and Medical Leave Act, although lacking paid leave and limited in other respects, is relatively comprehensive with regard to the types of leave covered. Many other countries, in contrast, built their policies on a platform of longstanding maternity leave and sick leave provisions, adding other types of leave, such as paternity and family care, as separate programs.

For that reason, among the OECD nations that offer paid family care leave, 40 percent offer compensation at varying monetary rates and for varying intervals of time, depending on who is ill and the severity of their medical condition. As mentioned above, the largest body of family leave research focuses on parental leave. Results from this research suggest that the existing state paid leave programs are effective at addressing the negative consequences associated with the lack of paid leave. Studies measuring the effect of state paid parental leave programs in the United States have found that 24 percent of women who took unpaid leave used public assistance during their leave period, while only 10 percent of women on paid leave did the same.

If employers provide eligible employees with paid sick leave for their own illness or injury or to receive health care, they must be allowed to use this accrued leave to care for their family members under the same terms and procedures that apply to any other use of the leave. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand has been a tireless advocate for national paid leave. Elizabeth is committed to adopting and building on Senator Gillibrand's work by fighting to make paid family and medical leave available to all workers.

Through FMLA, eligible employees take unpaid leave, whereas paid family leave is paid. The Federal Employee Paid Leave Act, which took effect in October 2020, grants federal employees 12 weeks of paid parental leave following the birth or placement of a child. The policy, part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, will apply to 2.1 million civilian workers employed by the federal government, though employees must have been in federal service for at least a year to be eligible.

While Congress addressed this need amid the pandemic by providing temporary emergency paid sick leave and emergency paid child care leave to some workers, the United States still lacks a permanent and comprehensive paid family and medical leave policy. This makes the United States the only industrialized nation in the world to not guarantee any paid leave for workers. Policymakers must act now to ensure that all workers have access to paid family and medical leave. This fact sheet provides key data on the need for, and widespread support of, a comprehensive paid family and medical leave policy. There also is evidence from parental leave studies to suggest that state paid leave programs improve caregiver mental health.

A group of four Democratic senators last week introduced legislation to provide federal employees with up to 12 weeks of paid family leave per year to handle illnesses and other circumstances not covered in paid parental leave benefits passed into law in 2019. The new legislation mirrors a bill already under consideration in the House. There is no federal requirement that employers offer employees paid sick leave when they or a family member has a short-term illness that does not permit them to work. In 2015, the Obama Administration issued an executive order that requires federal contractors to offer at least seven days of paid sick leave per year to their employees, on an accrual basis, which took effect in 2017. At the time of enactment, this applied to approximately 300,000 people working on federal contracts.

Furthermore, government employees have generally had access to paid sick leave through employee benefits packages. Introduced in Congress in 2019, the Healthy Families Act would require employers nationwide with 15 or more employees to provide at least one hour of earned paid sick leave for every 30 hours workers . Employees would be able to use sick leave for their own illness, to care for a family member, or to address needs resulting from domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking. Workers and their families experience myriad life events that require paid leave. For short-term medical needs such as a temporary illness or doctor's appointment, an earned paid sick leave law will allow workers to care for their own health or a sick loved one. For more serious medical or family caregiving needs, workers need access to long-term paid family and medical leave.

Family member means employees' child, stepchild, spouse, domestic partner, sibling, parent, parent-in-law, grandchild, grandparent, or stepparent. Personal sick leave benefits means any paid or unpaid time available to employees through employment benefit plans or paid-time-off policies for absences due to a personal illness, injury, or medical appointment. Employment benefit plans and paid-time-off policies don't include short-term or long-term disability benefits, insurance policies, or other comparable benefit plans or policies.

Employees can elect to substitute paid family, vacation, personal, or compensatory leave for unpaid family leave. They also can elect to substitute paid medical or sick leave for unpaid medical leave. In addition, employers and employees can agree to substitute paid vacation, personal, or compensatory leave for unpaid medical leave.

If employees want to substitute paid medical, sick, vacation, personal, or compensatory leave for unpaid family or medical leave, they must meet employer requirements for taking that paid leave. If employers have a leave program that permits an employee to use another employee's paid leave, that paid leave can be substituted for family or medical leave. Employers can't prohibit employees from using up to two weeks of accrued sick leave for family and medical leave for a family member's serious health condition or for the birth or adoption of a son or daughter. Employers also can't discharge, threaten to discharge, demote, suspend, or otherwise discriminate against employees for such use or attempted use of sick leave.

Sick leave means paid absences from work under employers' bona fide written sick leave policy, but it doesn't include other certain types of paid leave provided by employers' plan such as short-or long-term disability leaves. Ultimately, the results of the 2016 presidential and congressional elections will tell us more about paid family leave policies in the short term than in the long term. Even if leaders who are hostile to paid leave take power in 2017, the momentum for the issue will continue to grow as more states, cities, and counties adopt paid leave. Currently, only 13 percent of civilian workers in the United States have access to paid leave through their employer, but new companies are adopting generous leave policies on almost a daily basis. A recent poll of likely 2016 voters found that 79 percent say it is "important for elected officials to update the FMLA to guarantee access to paid family and medical leave." Politicians will eventually be forced to address the issue as public opinion continues to grow increasingly favorable to it.

Ensuring that all workers in the United States have access to the paid family leave that they need will not happen overnight; however, if we continue in the direction we are headed, it will happen. Family leave policies allow workers to take time off from their jobs to care for family members. Maternity leave is granted to mothers around the time of childbirth or adoption; paternity leave is reserved for fathers around the same time. After maternity and paternity leave end, parental leave provides gender-neutral leave for parents to care for small children. Many countries have separate programs that offer leave to care for a sick or elderly family member. In the United States, however, family leave policies often group together leave for new parents, leave to care for a family member with a serious illness or injury, and leave to care for an employee's own illness or injury.

The United States is one of very few countries worldwide without guaranteed paid parental leave at the federal level. The Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act , the only existing federal leave policy in the U.S., guarantees eligible employees of covered employers twelve weeks of unpaid leave in a 12-month period for specified family or medical reasons. But there are problems with the FMLA resulting in unequal access and low rates of usage.

FMLA issues include a narrow definition of family, requirement that businesses granting leave have more than 50 employees, and, most importantly, the fact that leave under FMLA is unpaid, and therefore burdensome for those who cannot afford the loss of wages. We see a guaranteed paid family leave scheme, funded through a national social insurance program, with supports for parents exiting and re-entering work and for businesses to ensure work coverage and smooth transitions, as a big part of solving the infant care problem in the United States. Paid family leave is currently how all other advanced economies resolve infant care, often with paid leaves for one or both parents of several months to a year or more.

Infant care is the most expensive kind of child care, because it requires more teachers with smaller groups of babies and more one-on-one care than does care for older children. The Care Index found that center-based infant care costs, on average, 12 percent more than care for older children. The Indexalso found that the average cost of center-based care for infants is more than the cost of in-state tuition at a four-year college in 33 states. More, the average cost for nanny care is more than three times the cost of college, more than half the median household income, and 188 percent of a minimum wage earner's income. Infant care is alsodifficult to find, as some providers close more expensive infant and toddler classrooms in order to stay in business. Workplace benefits are an important part of balancing work, family, and medical needs.

Benefits such as paid family and medical leave and sick leave can help employees meet their personal and family health care needs, while also fulfilling work responsibilities. The American Rescue Plan Act , enacted in March, doesn't require paid and emergency family leave. But the law does extend and expand the tax credits that were available under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act , incentivizing small and midsize employers to provide paid time off for FFCRA and new COVID-19-related reasons. Under ARPA, tax credits continue to be available for paid sick leave, paid family leave and other reasons. Ultimately, it would be extremely useful to understand the impact of existing laws—in particular, the new state paid family leave laws—on leave to care for a seriously ill family member. Has the availability of paid family care leave to care for a seriously ill family member improved the health and well-being of family members and of the employees who care for them?